“Provocateur,” “pervert,” “genius,” “pioneer” - indeed, writer and publisher Horst Schröder has throughout the years been subject to a variety of labels, some more flattering than others. However, opinions are less fractured when it comes to defining Schröder’s importance, and that of his publishing company, Epix Förlag, for the comics scene in Sweden. The eccentric and often uncompromising Schröder is in large part responsible for introducing comics aimed at an adult audience to a Swedish readership during the 1980s.

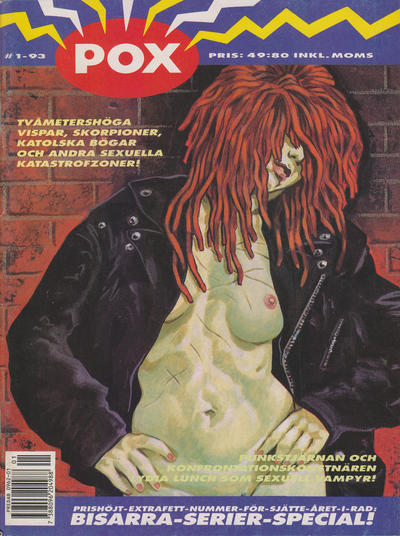

Through his many monthly titles, most notably Epix (1984-1992) and the slightly edgier Pox (1984-1993), Schröder published the familiar names and faces of American underground comix: Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Shary Flenniken. Later, he published the burgeoning alt-comics generation: Peter Bagge, Julie Doucet and the Hernandez brothers, as well as European alternative cartoonists such as F’murr, Joost Swarte, Édika and Didier Comès. Then there were feminist and gay comics by Sharon Rudahl and Ralf König, and gekiga by Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Kazuo Koike. Almost all of them made their debut on Swedish soil in one of Schröder’s magazines. But everyone was not swayed by what Schröder put out. Epix’s periodicals were critiqued for being a menace to public and sexual mores, an accusation that culminated with Schröder's prosecution on six counts of illegal depiction of sexual violence and coercion. Although he was acquitted of all charges, the trial marked the beginning of the end for Schröder’s magazines, as he lost both subscribers and distribution channels. The last Epix Förlag magazine was sold in 1993.

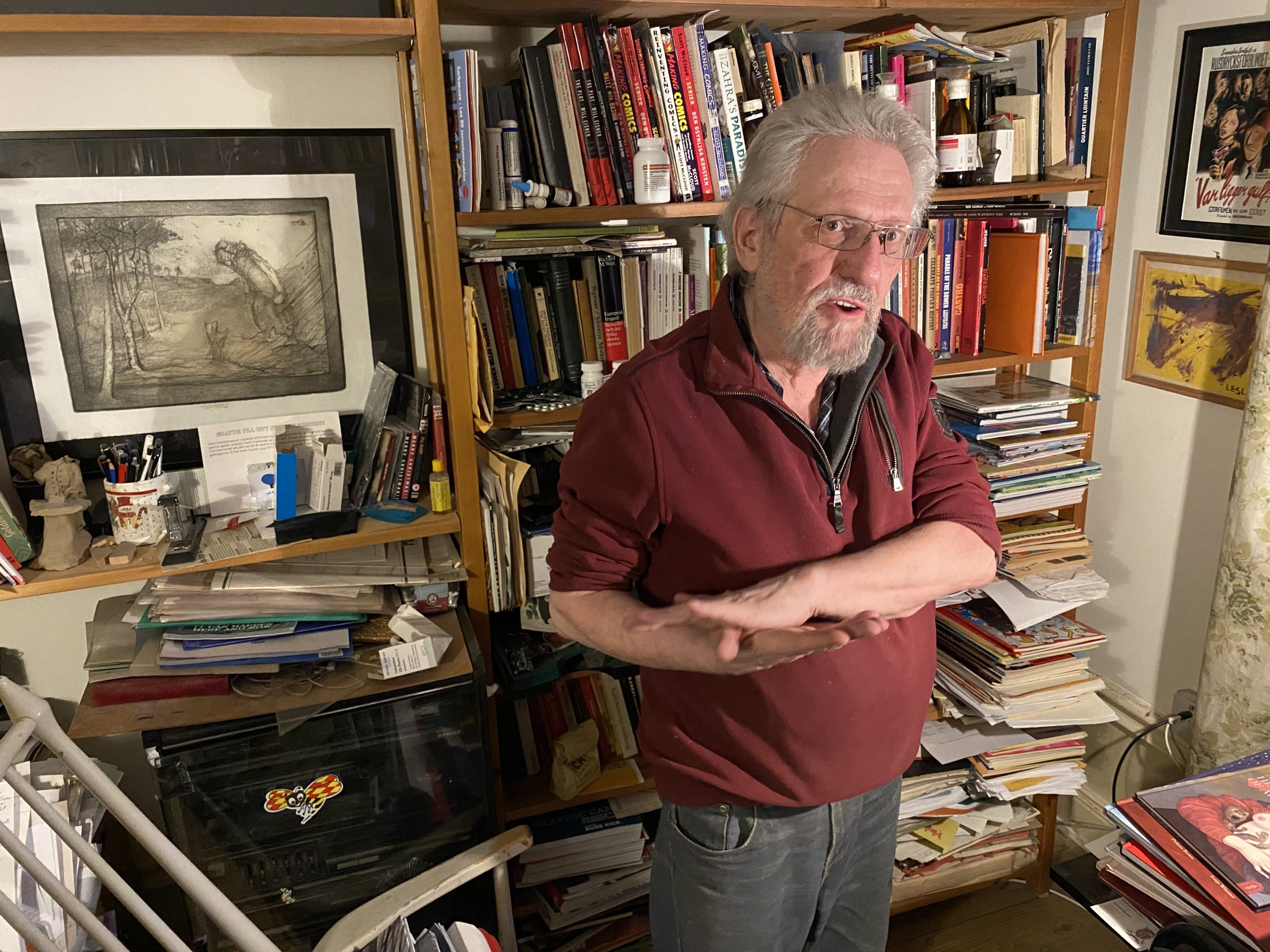

At age 80, and having battled serious health issues, Schröder is as energetic and outspoken as ever. He still lives in the same apartment in central Stockholm that he bought in the early 1970s - a property he pawned to launch Epix Förlag in 1984. Almost 50 years later, little has changed on the inside. Schröder spends his daily life in what vaguely resembles a second-hand bookstore: overfilled bookshelves, piles of comics spread out everywhere on the wooden floors, brown boxes on top of each other in various corners. In short, cozy - and with little space for a dust cloth. Notable is also the heat and a constant buzzing sound from one of the rooms. As it turns out, there is a perfect explanation to both the noise and the almost tropical indoor temperature: “I have sublet one bedroom to a Bitcoin company,” Schröder says. “They have their servers in there.” He closes the door to the bedroom, and we sit down at his kitchen table to look back on a life in comics publishing, including a drug deal, a kidnapping, and a trial.

Schröder was born in Köln (Cologne), located in western Germany, in 1943; he grew up in the aftermath of World War II, the oldest of five siblings. The family was impoverished, and Schröder remembers how he was teased at school as other children called him katzenfresser - “cat-eater.” “We probably ate cats,” Schröder admits. “A lot of poor families did back then.” The family’s financial situation was a direct consequence of denazification: a term often used to describe the process of removing Nazis and Nazism from public life in Germany following the fall of the Third Reich. Both his parents had been members of the National Socialist Party. His father had studied law, but was drafted before finishing his degree. After the war, due to his political sympathies, Schröder’s father was prohibited from continuing his studies. To put food on the table he tried his luck in various professions, including as a carpenter and a travelling language instructor. Despite their modest financial means, the children got a Donald Duck subscription for Christmas one year. Schröder lists Donald Duck, together with an album by Manfred Schmidt about his detective Nick Knatterton, as the two reading experiences that sparked his interest in comics.

As a graduate student in literature at the University of Frankfurt, he would rediscover his affection for Disney comics, especially those by Carl Barks. He also realized that only a mere fraction of all Disney comics had reached western Germany; there was a large body of published work available in America. Schröder got a subscription to Comics Buyer's Guide and started to import comics. “I bought an incredible amount of comics. Eventually I had probably close to 40,000-50,000 single issues,” Schröder recalls. “In those days, I definitely had Europe’s largest collection of American comics. It still sits in my basement and should be worth about eight to nine million [i.e. 800,000 to 900,000 USD] today.” Parallel to his intense comics collecting, Schröder moved to Sweden. During a visit in the early 1970s, he had fallen in love and settled in Stockholm. Although the relationship did not last, Schröder stayed put and started to make a name for himself on the local comics scene. By the end of the decade and during the early years of the next, he had his own byline in the major daily newspaper, Aftonbladet, under the header “The Comics Professor” where he addressed everything from Mickey Mouse to feminist underground comix. He also published two Swedish-language books about comics–the first detailing the history of the American newspaper strip comic, the second exploring American, British and French science fiction comics–while also dipping his toes in scriptwriting for his own comics, and editing Bild & Bubbla, the official trade magazine of the Swedish comics association Seriefrämjandet. But above all, he wanted to publish comics.

An opportunity arose in 1983, when he was approached by two Englishmen who published a music magazine called Soundtracks in Sweden. According to Schröder, they wanted him to write about popular German music, but when they visited him at home and saw his immense comics collection, they quickly changed their mind. Instead, they proposed that Soundtracks should include a couple of pages with comics selected by Schröder. The section with comics became so popular that they immediately decided to make an issue with only comics. “This was number zero to Epix,” Schröder explains. Soon after, the three of them decided to launch their own comics magazine. “Everyone was supposed to invest 100,000 each [roughly 10,000 USD]. I pawned my flat and got to work,” Schröder recalls. “I waited and waited on their hundred grand, but they never came up with any money. Later I learned that one of them had been pulled over by the police on his way to the airport with a trunk full of cocaine.”

I tracked down the other Englishman, who still lives in Stockholm. He confirms that his former boss got caught by the police for possession of drugs. He says that they have not had any contact since then, and that to his knowledge his fellow countryman was deported from Sweden after 10 years in jail. However, he denies having been involved in starting a comics magazine. Schröder remembers things differently. With one of the Englishmen behind bars, he requested payment from the other. “’I’ve never had any money’ he responded,” according to Schröder. “I was stuck with a half-finished magazine and a pawned flat. I could either give up and lose my home, or take another loan and a leap of faith. I opted for the latter.”

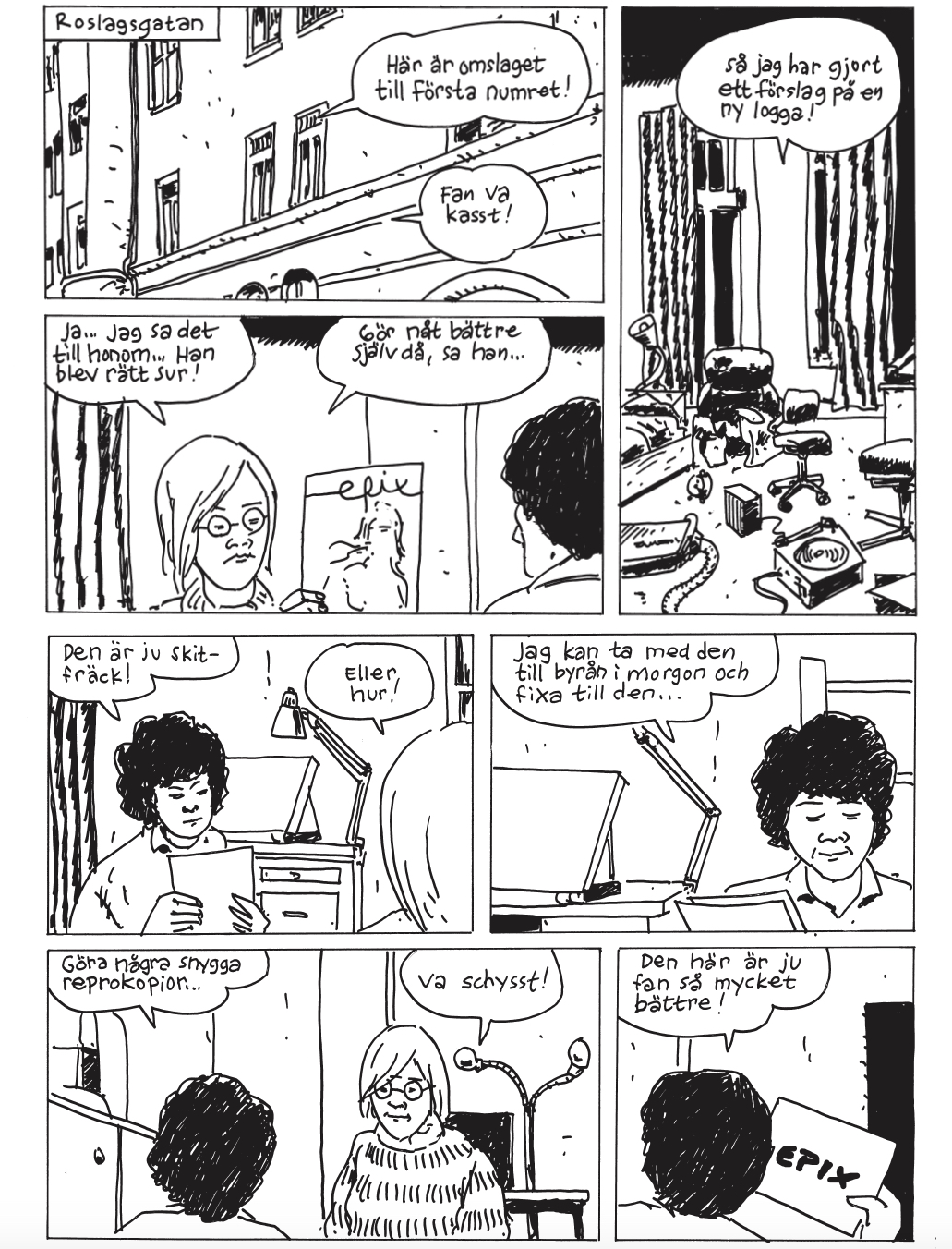

Schröder recruited a group of friends to help him put together what would become the first issue of Epix - among them Göran Ribe and Johan Andreasson, with whom he had shared editorial duties at Bild & Bubbla, and a young cartoonist named Gunnar Krantz, who set down the layouts for the magazine and designed its logo. “Horst showed me the logo he had done, and I told him that it looked awful,” Krantz recalls in his office at Malmö University, where he nowadays is a professor in visual communication. “He got a bit annoyed and said ‘Do something better yourself,’ so I started drawing a new logo for the magazine. I also remember that Horst insisted on having ‘Comics for Adults’ printed on the cover, which I thought sounded a bit corny.”1

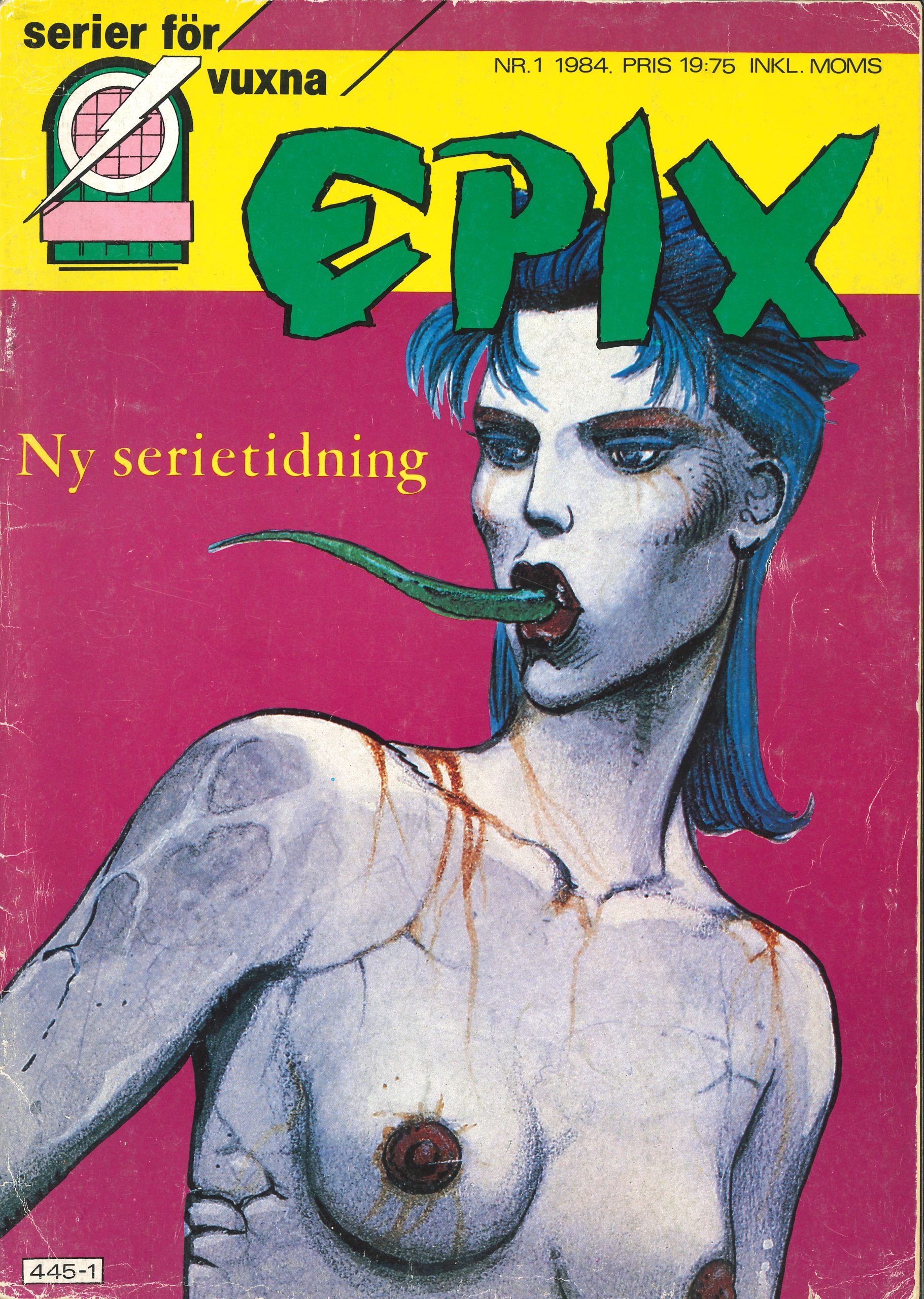

The first issue of the publisher's eponymous magazine, Epix, was released in Spring 1984. It contained comics by Gotlib, André Franquin, Moebius, Christian Binet and others. In a lengthy editorial, Schröder writes that Epix aims to offer its readers the best from the European market. Thus, the content to a large degree mirrors what was being published in other parts of the continent, as comics magazines aimed at adults had been flowering since the mid 1970s. Sweden was no exception. Akin to several other European countries, Sweden had a distribution system in place that made new magazines available at newsagents and kiosks. But perhaps more importantly, there was an audience who had grown up reading comics, and to whom there was a natural continuity, rather than a cultural stigma, to read adult comics.

Schröder and Epix were not the first to try their luck at pushing material orientated towards an adult readership, nor were they alone in the market. Already in 1979, three new comic anthologies saw the light of day–Mammut, Svenska Serier and Galago–that all targeted a more mature audience, and thereby clearly distinguished themselves from the superheroes or anthropomorphic ducks that otherwise dominated kiosk shelves at the time. While both Mammut and Svenska Serier quickly folded,2 Galago still publishes today an important forum for alternative comics. Although Schröder had several public feuds with Galago’s editor, Rolf Classon, their respective publications had different focuses. Where Galago to a large degree attracted a pool of domestic talents, the common thread that ran through Schröder’s publications was their international outlook. In that regard, Epix’s publications had a closer kinship with Métal hurlant and Fluide glacial in France, El Víbora in Spain, or Alter in Italy. These publications are acknowledged by Schröder in his editorial, as he attempts to pinpoint what makes Epix unique in a Swedish context.

Despite his confidence in the quality of the magazine, Schröder was convinced that his company was doomed from the outset. His financial estimation was that Epix would not survive for more than three issues. Much to his surprise, the first issue sold 11,000 copies, far exceeding the 3,000 they needed to break even. Göran Ribe, Schröder’s closest collaborator, credits the commercial success to Gunnar Krantz’s marketing plan of paying for advertisement space in Stockholm’s subway. Although the subway ad itself was nothing else than the actual cover to the first issue–a drawing by Enki Bilal of a naked, lizard-tongued Medusa with a little text added–it drew necessary attention to the magazine, Ribe says. For the next issue, they wanted to advertise on trash cans around Stockholm, but the ad was refused due to the cover by Régis Franc, drawn in a cartoon style, of a woman sitting on a bed and wearing a décolletage. It was deemed too sexual.

Instead of being upset with the decision, Krantz remembers that Schröder was absolutely thrilled that he had successfully managed to provoke the City Council enough for them to ban him from advertising. According to Krantz, Schröder took a certain pleasure in obstacles, especially when he felt that people and institutions were against him. The outsider position he promoted for himself would become as associated with his name as his hot temper and constantly fuming pipe. In his seminal work on the subject, Colin Wilson writes that characteristic to the outsider is a sense of strangeness, a feeling of alienation in the face of an insulated bourgeoise society.3 Criticism of his publications, a lukewarm review, or simply being banned from advertising on trash cans were all in Schröder’s eyes confirmations of his status as an outsider, as someone whose actions and work aggravated the establishment.

More unexpected objections to the content of Epix came from the printing house. They found the comics so offensive that they refused to print any further issues. Schröder not only found a new printing house in Finland, he also discovered that their fees were substantially lower. When the second and third issue of Epix also returned a profit, Schröder realized that the reduced printing costs gave him enough financial leverage to launch a new magazine. The inaugural issue of Pox, a publication devoted to more avant-garde comics and selections from the American underground, was published in black-and-white the same year, in the fall of 1984; it would become Schröder’s personal favorite among his many publications. “It is not like I didn’t like the comics I published in Epix, but Pox is somewhat the closest to my heart,” he explains. However, when the first issue's shipment arrived from Finland, Schröder discovered that the cover did not have the mandatory return bar code. Krantz recalls that they all had to go down to the docks and manually stamp a bar code on each copy - all 20,000 of them.4

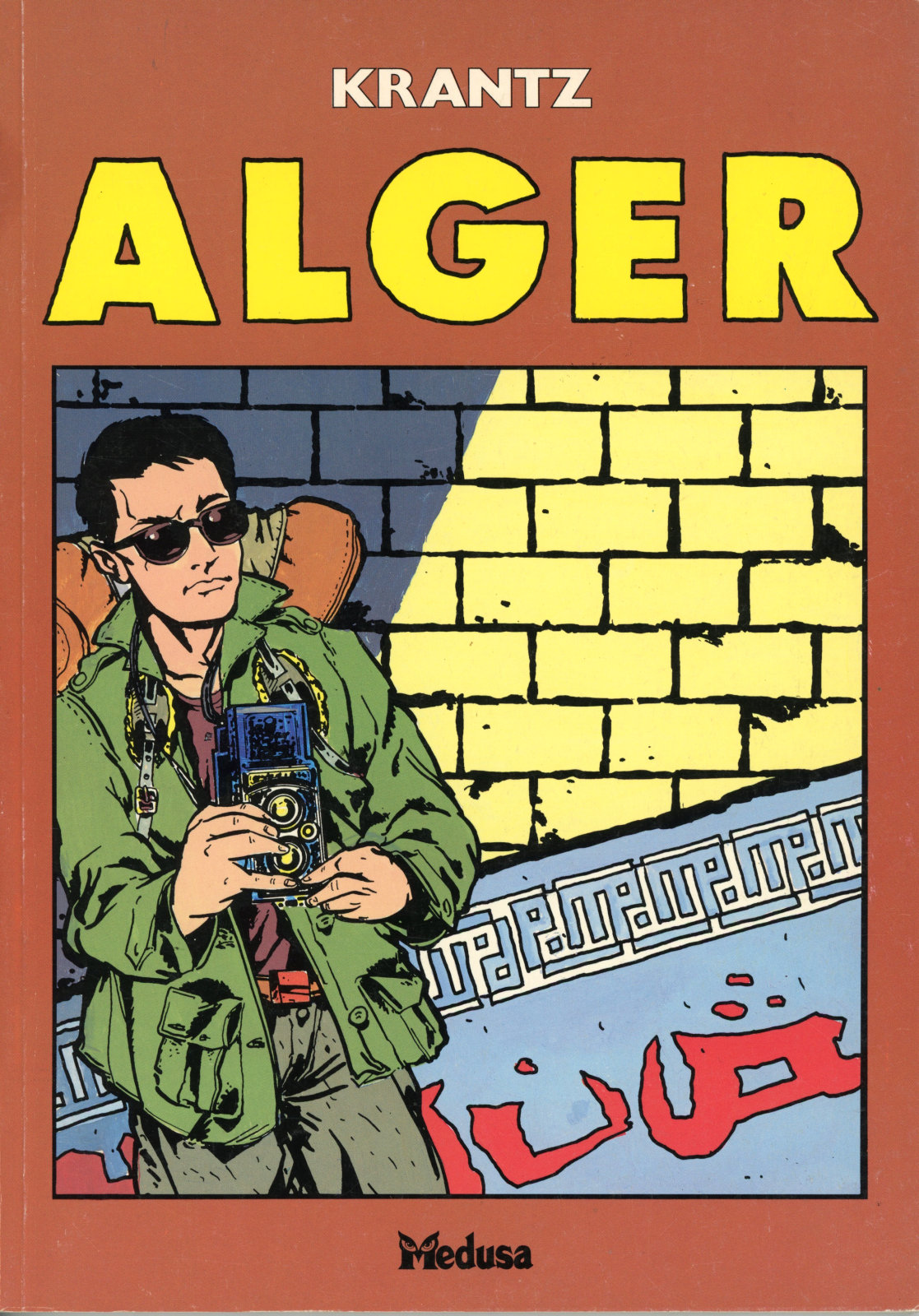

The first issue of Pox contained comics by R. Crumb, Howard Cruse, Joyce Farmer, Rick Geary, Bill Griffith, Jose Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo, Trina Robbins, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton and others. Later issues included the likes of Aline Kominsky, Joe Sacco, Art Spiegelman, Philippe Vuillemin, S. Clay Wilson, Jim Woodring, Wolinski and Dori Seda. But it also serialized Krantz’s award-winning album Alger, about the relationship dynamics between two friends who hitchhike from Sweden to Algeria in the 1950s during the Algerian War of Independence.5 “Horst visited me at home while we were preparing the first issue of Pox,” Krantz says. “He saw a few inked pages that I had drawn. He started reading and then said ‘we’ll run this in the next issue.’”

Schröder contends that Epix pioneered the autobiographical genre in comics to a Swedish audience, in that Alger is Sweden’s first work of autobiographical comics, a claim that Krantz himself only partly agrees with: “For starters, I was not even born in the 1950s where the plot is set,” Krantz explains. “I was fascinated by the conflict between France and Algeria. I read the script to the The Battle of Algiers, the movie by [Gillo] Pontecorvo, and studied the historical background to the conflict. From this, I construed a plot that also borrowed from [Wim] Wenders' movie The American Friend, about finding yourself in a situation impossible not to be drawn into. But there are, of course, autobiographical elements to the story based on my own experiences from an interrail trip with a friend.”

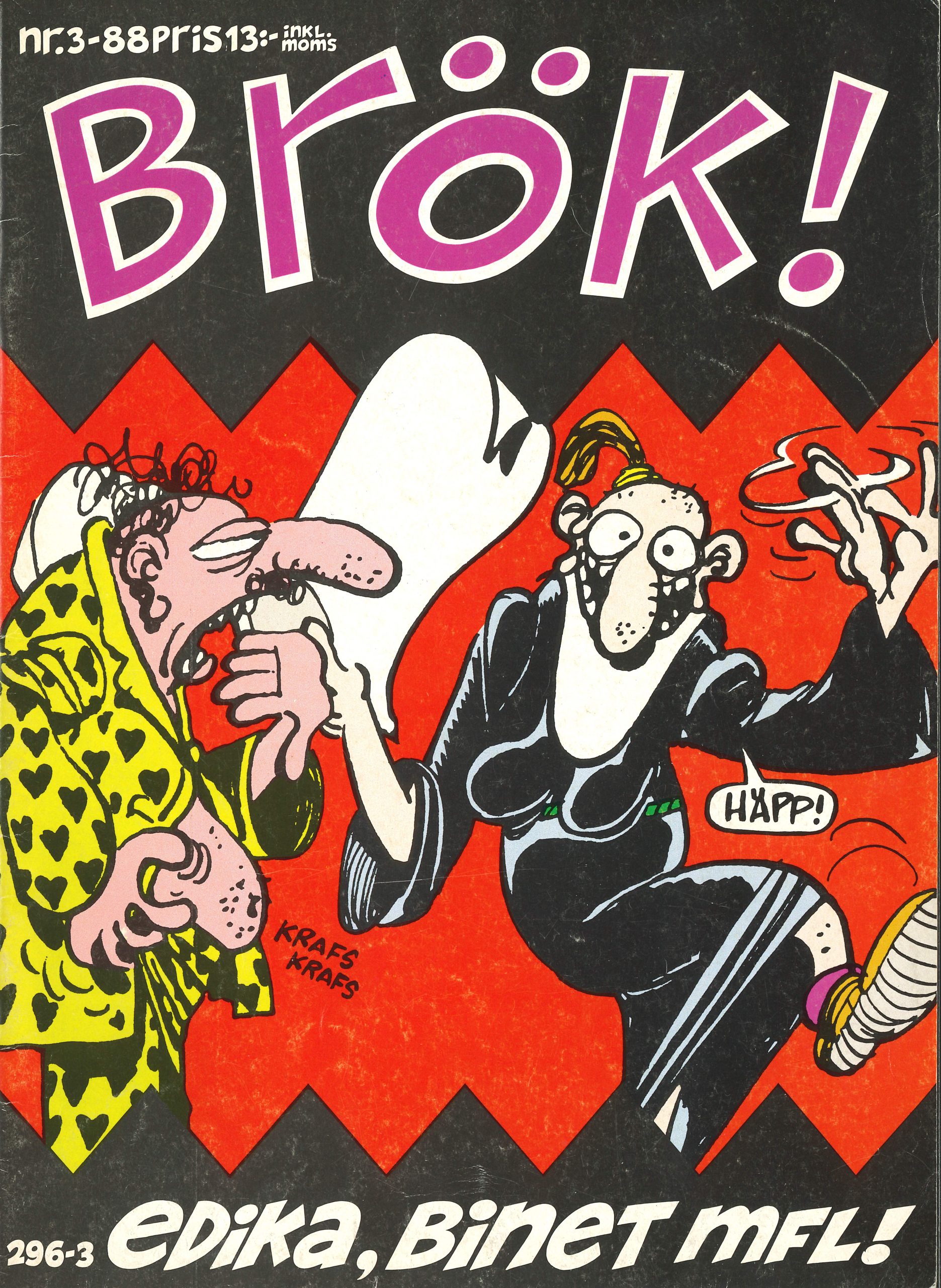

Schröder’s entrepreneurial energy continued to flourish throughout the 1980s. He expanded quickly with new offices for the editorial staff, and opened a comic bookstore alongside his already existent imprint, Medusa, which published albums of individual stories that had been filtered out of his magazines. And he had many to choose from, as he continued to launch new publications. After Pox came Tung Metall (1986-1990), a Swedish version of the French Métal hurlant, filled with science fiction and fantasy comics; Maxx (1986-1987) with action comics; Samurai (1988-1992) with manga and gekiga; Casablanca (1987-1988) with adventure comics; Elixir (1986-1987) and Brök! (1988-1991) with humor comics; and Topas (1988-1994) with erotic comics, to name but a few. In 1987, Epix’s magazines sold a combined total of 27,000 copies per month; by then, they had 12 employees on the payroll.6

What unified all Schröder’s publications was the strong presence of the publisher himself. Schröder would devote a great deal of editorial space in his magazines to reflect upon the content of the comics, developments in the industry at large, and the hardships of being a publisher, in addition to commentary on current events in Sweden, the world, and his private life. The tone is often didactic—at times preachy—as Schröder recurrently critiques what he considers to be signs of an unsophisticated approach to comics among a Swedish public in need of education to overcome their preconceptions about comics as a juvenile pursuit. “But it was all true!” Schröder contends, close to 40 years later. “Sweden was a wasteland when it came to comics.” At the same time, the paucity of adult comics published in Sweden was also a commercial advantage. “I basically had 20 years of international comics publishing to take from,” he admits, adding that another advantage came from his fluency in eight languages, which enabled him to read what was being published across Europe and North America.

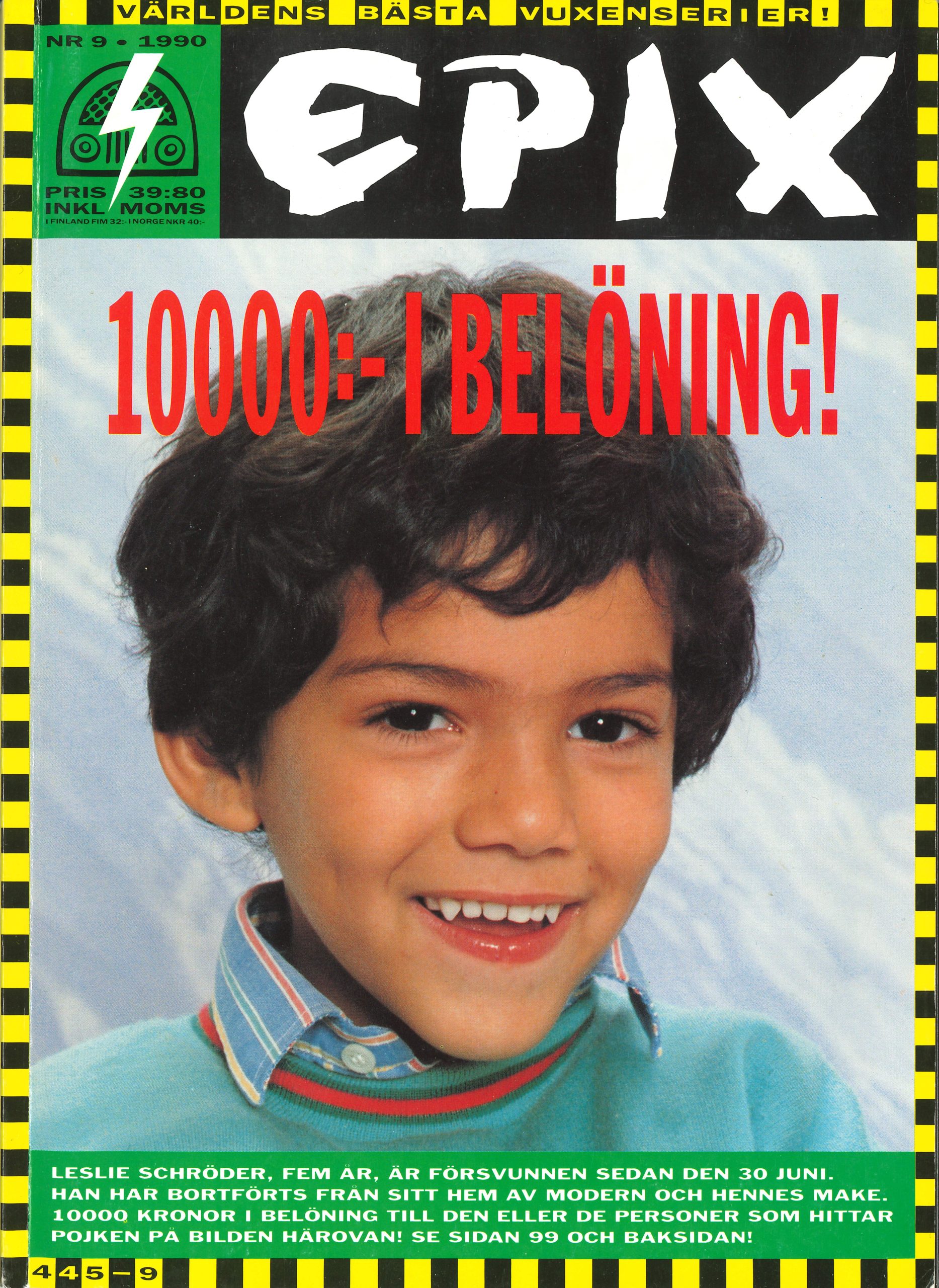

In his historiography of Swedish comics, critic Nisse Larsson argues that Schröder invented a new literary genre with his editorials, and that these texts alone merit him a chapter in the history of Swedish writing.7 Per Larsson, the editorials are “great literature,” blurring the boundaries between public and private, as Schröder invites the reader into the intimacy of his home and lets them access his most inner thoughts. A case in point occurs in 1986, when Schröder devotes editorial space to describe his emotional state after separating from his son’s mother. And there is no clearer example of the ways in which his editorials eradicate the border between public and private than Schröder’s writing during the months after the abduction of his six-year old son, Leslie, in 1990.

Schröder had been granted full custody of the child, but Leslie did not return from a visit with his mother. Instead, the child’s mother and her new husband had disappeared. When the authorities were unable to help Schröder, he desperately responded by posting a photo of Leslie on the cover of Epix and offering a cash reward to anyone who could supply leads on the boy’s whereabouts. The back cover included a detailed description of Leslie, but also descriptions of the alleged kidnappers: names, photos and social security numbers. This controversial and ethically dubious method was successful, providing him with clues that advanced the case further than the police had achieved at that point. Schröder was contacted by a man who had recently sold a sailing boat to Leslie’s mother’s new husband. The boat was later discovered on the Spanish island of Tenerife. “I was notified by Interpol while I was at the Frankfurt Bookfair,” Schröder says. “They thought that the kidnappers had made their way to the Caribbean.” Schröder retained a British firm specialized in kidnapping cases, and paid for a private investigator to search for the boy in Trinidad, where relatives to the boy’s mother lived. “When I went there myself, it turned out that the private investigator was drunk as hell, had spent a shitload of my money on cab fares, and had the whole time been spying on the wrong house,” Schröder laments. He got better help from a local detective who called in a few favors, and Schröder was soon reunited with his son again. In the ensuing issue of Epix, the editorial is titled “Happy resolution to the drama,” as Schröder, in great detail, recounts every step of how he managed to locate Leslie and get him back. Father and son celebrated with a visit to Disneyland before returning to Sweden.

Another incident occurred in 1989, when the Chancellor of Justice decided to prosecute Schröder and an issue of Pox on six accounts of illegal depiction of sexual violence, due to a new Article in the Freedom of Press Act that had been introduced the same year to combat violent videos and photographs.8 Five stories were cited in violation. All of them were published in the 1/1989 issue of Pox:

1. “Journey to Bethlehem” by Neil Gaiman & Steve Gibson. The comic depicts an event from the Book of Judges where a woman is raped and killed by a group of men.

2. “Fe” by Damián Carulla. A dystopian BDSM comic.

3. “A Mother’s Heart!” by Andrea Pazienza. Three young men take advantage of a mother by blackmailing her to have sex with them, lest they spread rumors about her daughter at school.

4. “Vegetable Lover” by Karen D’Amico & Michael T. Gilbert. A female nurse, who has been mistreated by men her whole life, has sex with a man in a coma.

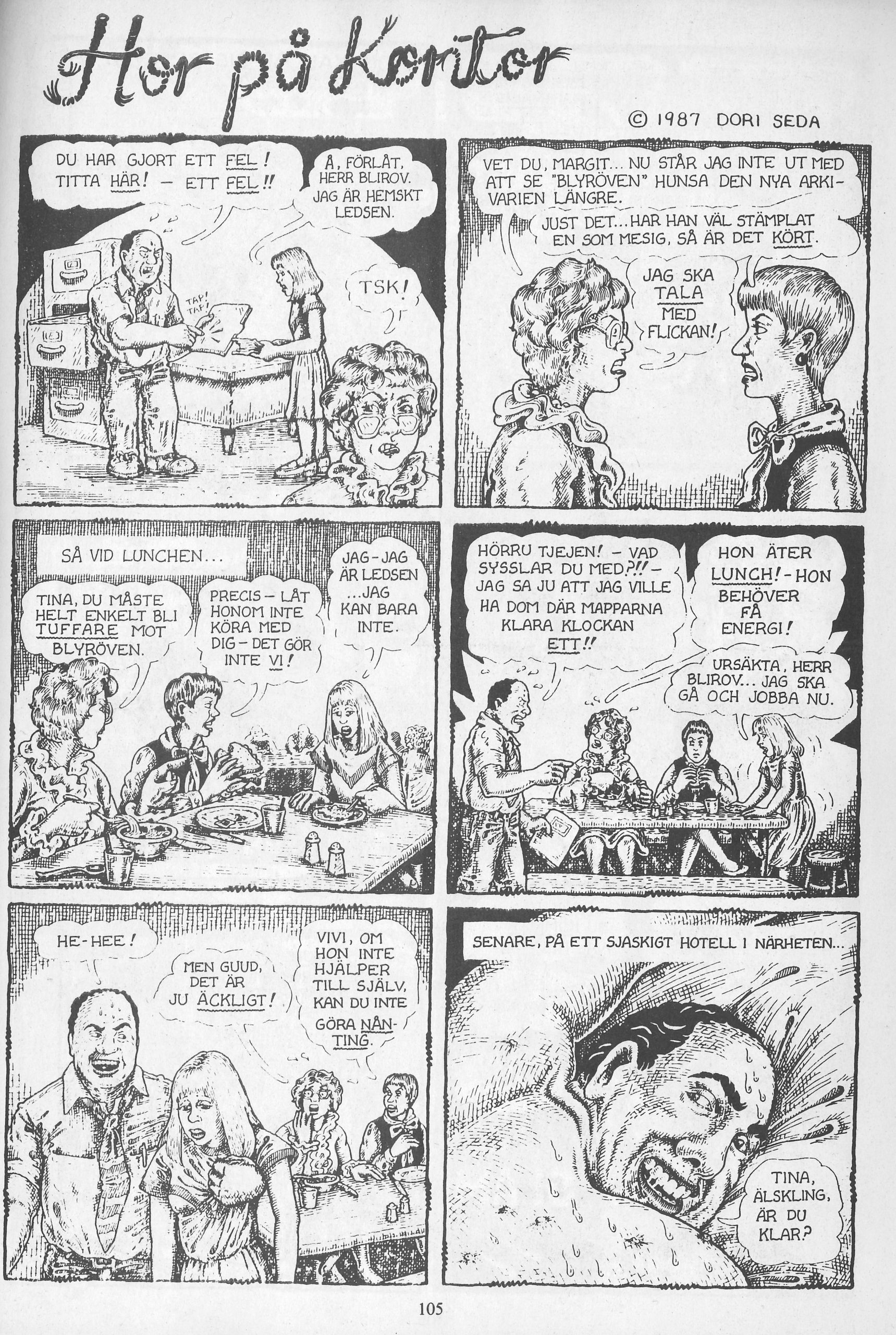

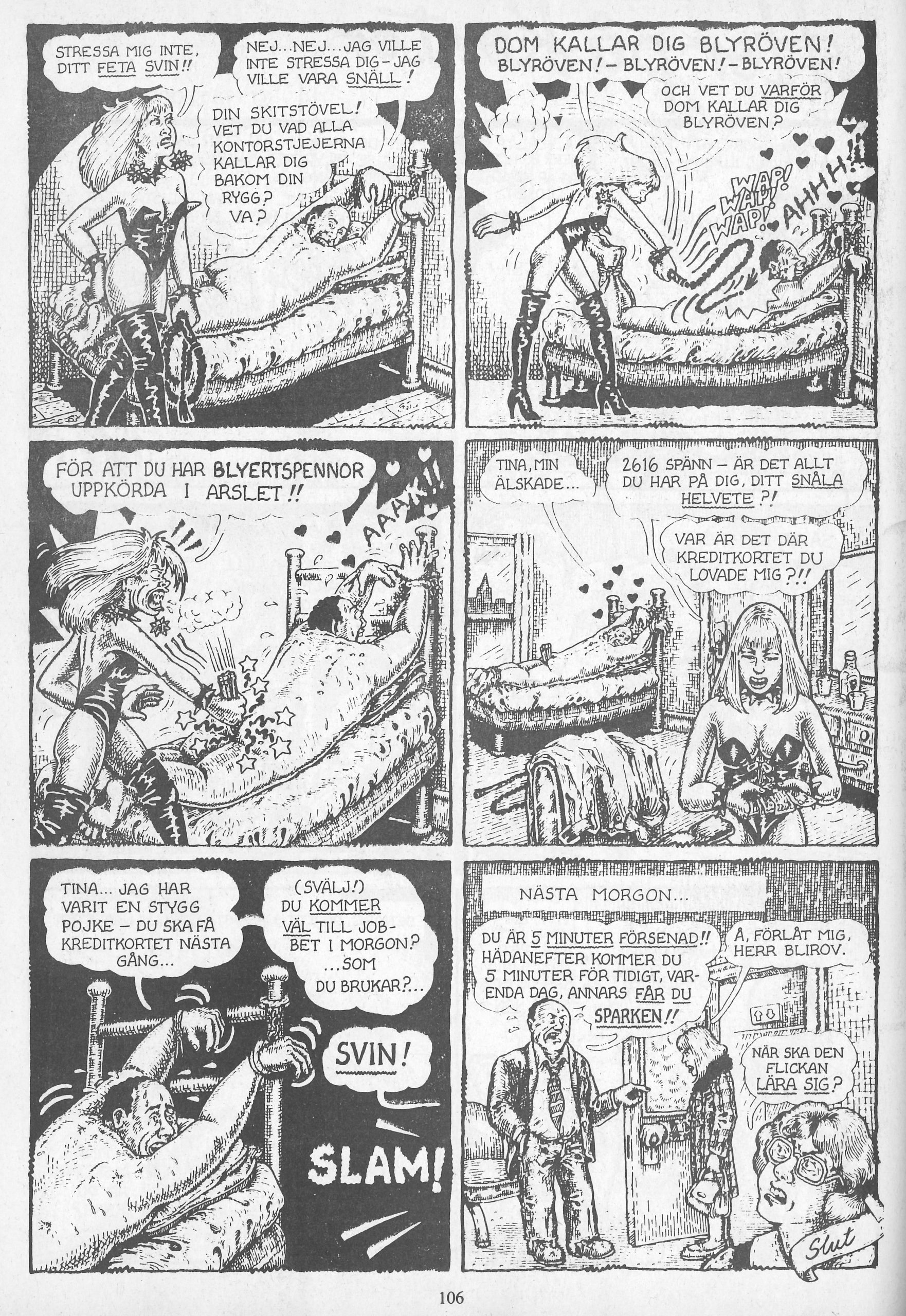

5. “Office Tops and Bottoms” by Dori Seda. A secretary, timid and submissive during the day, sexually dominates her boss at night.

As a direct response to the prosecution, Schröder republished all the accused comics alongside various essays on censorship as part of a special edition of Pox titled Åtalad! (“Prosectuted!”) in late 1989. “The comics that were prosecuted were avant-garde adult comics for a very small adult audience,” Schröder says. “I would have understood if they had prosecuted the content in Topas that actually was pornography.” Although Topas–Epix’s equivalent to Fantagraphics’ Eros line of erotic comics–was the most explicit example, most of Epix’s periodicals carried material with sexual content, which did not go unnoticed among contemporary critics. The very first issue of Epix had been described by the daily newspaper Expressen as a cocktail of “social criticism, satire, and porn. A lot of porn.”9 Other outlets made similar observations. Bild & Bubbla praised Schröder’s magazines for their rich selection of predominately European comics, mixing raw humor and action-packed thrillers with cruel animal fables; but they also noted that the magazines contained plenty of “pornographic creations that seem to imply a male readership.”10 Epix was far from alone. The content reflected a general trend in European comics devoted to an adult readership at the time - no small part of it was filled with sexualized imagery. According to comics scholar Roger Sabin in his 1993 book Adult Comics, European comics in the mid '80s were, to a certain extent, dominated by sex-erotica;11 such comics were “Europe’s trashy equivalent to the American superhero,” as Gary Groth put it in an issue of The Comics Journal from 1985.12 Some of the content in Schröder’s periodicals certainly lived up to these statements.

The trial took place over two days in January 1990. Witnesses were called to judge whether the comics in question were defensible for reasons of aesthetic value.13 The defense strategy, specifically emphasizing Gaiman’s and Gibson’s comic as a direct adaptation of passages from the Bible, was to highlight the absurdity in trying to prohibit a subject matter when depicted in pictures, while permitting it when described in words. The jury agreed, and acquitted Schröder on all charges. But the trial left a stamp on him as a publisher of pornography. His periodicals lost readers, and one of Sweden’s major grocery firms refused to carry any of Schröder’s publications, suggesting that they were “violent” and “pornographic.”14

At the same time, Gunnar Krantz, who by then had left the company, suggests that bankruptcy was always in the cards for Epix, claiming that the company was built on an unsustainable financial model. Only a few of the periodicals ever turned a profit; most of them never did, Krantz says. Yet Schröder was reluctant to cancel any titles. While admitting that he almost took pride in publishing what major publishers dismissed as completely unprofitable, Schörder justifies his actions by stating that there is a simple reason to why his business decisions often went against the grain of what would have been wise from a financial standpoint: “I never entered this business to get rich,” he says. “I was a missionary who wanted to promote cheeky, raw, political and provocative comics.”

He still does. Since 1994, albeit in a limited capacity, Epix has continued to publish a few albums every year. Despite having passed retirement age a long time ago, Schröder has no plans to step away from the industry. He insists there are still too many comics that he wants to publish - specifically the collected Sandman by Gaiman and others, and a book by the American historian Howard Zinn in comic form. Schröder adds that he also has a long list of titles to which he holds the rights, but has yet to publish due to either a lack of financial means or manpower. “If I had more co-workers, I would have published as much now as I did when I had my magazines,” he asserts.

Still looking forward, Schröder is reluctant to speak about his deeds in the past tense, as if any discussion on his legacy would imply that he does not have more to offer the Swedish comics scene. Nonetheless, and with uncharacteristic modesty, Schröder asserts that he, as a publisher, has meant nothing, but that his publications have hopefully meant something. “Comics in Sweden has probably received plenty of inspiration in various genres,” he summarizes, while finishing his coffee. “Science fiction, epic adventures, underground, autobiography, you name it. I published it all.” Krantz, meanwhile, says that Epix not only opened the door to the world by introducing a whole new rage of comics, but also let Sweden catch up with the dominant comics cultures in France, Belgium and the USA. “It was practically a tidal wave in the 1980s. All the major European names, plus American undergrounds and manga was published in Swedish,” Krantz says. “Horst introduced us to all of it.”

* * *

- Gunnar Krantz depicted the early days of Epix in his 2020 fanzine Comics from Siberia. The fanzine can be download from Krantz’s webpage, Seriekonst, free of charge.

- Mammut was published by a nonprofit association called Fria Serier. Svenska Serier, on the other hand, was published by Semic Press–a Swedish equivalent to Marvel or DC–and lasted until 1982. It was resurrected in 1987, then folded for good in 1996.

- Wilson, C. (1956) The Outsider. Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- According to Schörder, there were 10,000 copies; meanwhile, Krantz remembers that there were 30,000. However, in Comics from Siberia, Krantz writes that there were 20,000 copies.

- Alger was awarded the “Urhunden” in 1987, the Seriefrämjandet’s annual award for best Swedish album.

- Britton, C. (1987) “Vrooom: I serieförläggarens favoritalbum är ingenting heligt eller tabu,” Dagens Nyheter, April 19.

- Larsson, N. (1992) Svenska serietecknare. Alfabeta.

- Lindsköld, L. (2020) “So bad it should be banned,” Forbidden Literature: Case Studies on Censorship, Kriterium.

- Helmertz, F. (1984) “Blunda barn! Här är serietidningen för mamma och pappa,” Expressen, May 19.

- Kjellberg, S. (1984) ”Recension: Pox,” Bild & Bubbla, no. 5-6.

- Sabin, R. (1993) Adult comics, Routledge.

- Groth, G. (1985) ”Paradise Lost,” The Comics Journal, 96, p. 6.

- Lindsköld, L. (2020) “So bad it should be banned,” Forbidden Literature: Case Studies on Censorship, Kriterium.

- Siverbo, O. (1991) “Nix, Pox och Epix: KF Väst stoppar Schröders serier,” Göteborgs-Posten, November 25.